Standalone Reusable Apps

Standalone Reusable Apps#

1. Defining the scope of a Django standalone app#

Benefits of standalone app:

- Sharing your work - open source

- Imrpoved code quality

- Don’t repeat yourself

- Django’s

contribmodule already has many reusable apps - Commonality across company

- Commonalities across client projects

- Currency of prestige - attracting clients etc.

Ask yourself:

- Does your package need to be a django app or can it just be a python package?

- How django specific should it be if it isn;t to be a django app?

For example additional form fields would be a python package and not live in INSTALLED_APPS.

Don’t narrow your audience to force django - if it is not necessary.

Where it makes sense, reference the standard library instead of Django utilities. If something moves in a new Django version, you’re now insulated from that change.

When adding dependencies ask:

- Does the dependency provide necessary functionality for your app?

- Is it up-to-date with the Django version(s) you will be supporting?

- What kind of test and documentation coverage does it have?

- How committed do the maintainers seem?

2. Structuring Standalone Django Apps#

Django Apps as Python Modules#

A django app is a python package - multiple modules that can be imported from other packages.

A django app can only be used in a django project if they are in INSTALLED_APPS.

Having the package available in your python path is not sufficient.

A django app contains:

- models

- template tags

- templates directory

- static assets - css, js

- management commands

- default AppConfig class

For example an app for template tags would have:

boo

--- __init__.py

--- templatetags

|---__init__.py

|---boo_tags.py

to make use of it:

INSTALLED_APPS += 'boo'

You can include URLs, middleware classes, forms, and even views from any Python package, whether it’s a Django app in your INSTALLED_APPS or a Python package available on your path.

If the package has template tags - it has to be a django app

Example App: Currency#

currency

--- __init__.py

--- apps.py

---| template_tags

| __init__.py

| currency_tags.py

| tests.py

In order to satisfy the requirements of a Django app, our package must define a models.py file or an apps.py file

The __init__.py files are empty for now.

The apps.py file:

from django.apps import AppConfig

class CurrencyConfig(AppConfig):

name = 'currency'

verbose_name = 'Currency'

In currency_tags.py:

from django import template

register = template.Library()

@register.filter

def accounting(value):

return "({0})".format(value) if value < 0 else "{0}".format(value)

In tests.py:

import unittest

from currency.templatetags.currency_tags import accounting

class TestTemplateFilters(unittest.TestCase):

def test_positive_value(self):

self.assertEqual("10", accounting(10))

def test_zero_value(self):

self.assertEqual("0", accounting(0))

def test_negative_value(self):

self.assertEqual("(10)", accounting(-10))

3. Testing#

Tests ensure our code does what we expect. It also ensures that changes don’t break existing functions.

You should already know why testing is good.

In django projects, tests are run with python manage.py test

A single tests.py example:

from django.test import TestCase

from myapp.models import SomeModel

class TestSomeModel(TestCase):

def test_str_method(self):

instance = SomeModel()

self.assertEqual(f"{instance}", "<Unnamed Instance>")

Testing the App#

In a python package there is usually a tests module and a setup.py file defining a test script to run with setup.py test

The same with django apps but most of the tests must be ruin from the context of a django project.

It is not wise using an actual django project, and testing from the manage.py context.

Testing outside of a Project#

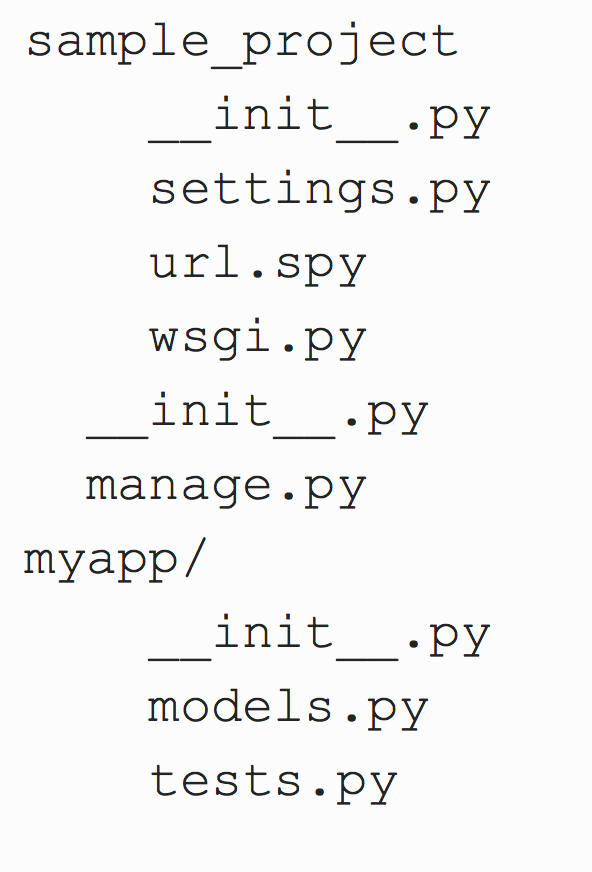

Create a new django project in our app’s root folder.

The project will then include the app in the INSTALLED_APPS list.

Then running tests is as simple as running manage.py

A stripped down project including only our app.

Example layout:

Then you run tests from the example project:

python manage.py test myapp

Using a Testing Script#

Django doesn’t demand that we have project scaffolding, just that Django settings are configured

So a better solution is a Python script that configures those minimalist settings and then runs the tests.

- Define or configure django settings

- Trigger django initialisation with

django.setup() - Execute the test runner

For settings we can use settings.configure() or a test settings file.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

import django

from django.conf import settings

from django.test.utils import get_runner

if __name__ == "__main__":

settings.configure(

DATABASES={"default": {

"ENGINE": "django.db.backends.sqlite3"

}},

ROOT_URLCONF="tests.urls",

INSTALLED_APPS=[

"django.contrib.auth",

"django.contrib.contenttypes",

"myapp",

],

) # Minimal Django settings required for our tests

django.setup() # configures Django

TestRunner = get_runner(settings) # Gets the test runner class

test_runner = TestRunner() # Creates an instance of the test runner

failures = test_runner.run_tests(["tests"]) # Run tests and gather failures

sys.exit(bool(failures)) # Exits script with error code 1 if any failures

Or using a tests/test_settings.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import os

import sys

import django

from django.conf import settings

from django.test.utils import get_runner

if __name__ == "__main__":

os.environ['DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE'] = 'tests.test_settings'

django.setup()

TestRunner = get_runner(settings)

test_runner = TestRunner()

failures = test_runner.run_tests(["tests"])

sys.exit(bool(failures))

Testing Application Relationships#

What happens when you want to use django with another app. Testing your app in isolation will not work.

You need to create sample apps and include them in your test settings.

For example allow people to make a product out of any model they want:

class ProductsQuerySet(models.QuerySet):

def in_stock(self):

return self.filter(is_in_stock=True)

class ProductBase(models.Model):

sku = models.CharField()

price = models.DecimalField()

is_in_stock = models.BooleanField()

class Meta:

abstract = True

To test this we need a concrete model:

test_app/

----/__init__.py

----/migrations/

----/models.py

In that app’s models, make use of the abstract base model:

from myapp.models import ProductBase, ProductQuerySet

class Pen(ProductBase):

"""Testing app model"""

name = models.CharField()

pen_type = models.CharField()

objects = ProductQuerySet.as_manager()

then include it in INSTALLED_APPS:

INSTALLED_APPS = [

'myapp',

'test_app',

]

Test or test folders within apps will work but should generally be avoided.

Tests should live in a seperate top level module outside of your app. This ensures there are no dependencies on non-installed modules - within the code that ships with your app.

/my_app/

----/__init__.py

/test_app/

----/__init__.py

/tests/

----/__init__.py

Testing without Django#

If your app doesn’t have any models, and you don’t have any request-related functionality to test - especially at an integration test level - then you can forgo with setting up or using Django’s test modules, sticking to the standard library’s unittest, or any other testing framework you so choose.

Testing features like forms, the logic in template tags and filters and others, is not dependent on any of the parts of Django that require project setup

4. Model Integrations#

If your standalone app includes concrete models, then you’ll need to include migrations with your app

In a normal django app you use:

./manage.py makemigrations

However we don’t have a project from which to run the migrations command - when building a reusable app.

In your project root, create a manage.py file - it should look very similar to the standard django manage.py:

import sys

import django

from django.conf import settings

INSTALLED_APPS = [

"django.contrib.auth",

"django.contrib.admin",

"django.contrib.contenttypes",

"django.contrib.sites",

"myapp",

]

settings.configure(

DATABASES={

"default": {

"ENGINE": "django.db.backends.sqlite3",

}

},

INSTALLED_APPS=INSTALLED_APPS,

ROOT_URLCONF="tests.urls",

)

django.setup()

if __name__ == '__main__':

from django.core.management import execute_from_command_line

execute_from_command_line(sys.argv)

Testing Migrations#

It is best to ensure the makemigrations have been run before commiting and that can be done in a test:

from django.test import TestCase

from django.core.management import call_command

class TestMigrations(TestCase):

def test_no_missing_migrations(self):

call_command("makemigrations", check=True, dry_run=True)

The check flag makes the command exit with a failing, nonzero status if there are any changes detected

Additional Migrations Guidelines#

If you’re not in the habit of descriptively naming your migrations, creating a standalone app is a good opportunity to pick up the habit.

Do like this:

./manage.py makemigrations myapp -n add_missing_choices

A good guideline for migration names is to treat them like even more concise Git commit message subjects: (i) what kind of change was made (e.g., adding, updating, removing) and (ii) the subject of the migration itself.

5. Templates#

Templates in standalone app is the same as in a normal app - but important to name and optimise templates for developers.

3 options:

- Do not include the templates - makes it obvious where users of app should add templates

- Include basic html templates

- Include detailed and stylised templates

Good to give an example:

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<h3>Here is a list of other fruits reported by the app</h3>

<ul>

{% for fruit in fruit_list %}

<li class="fruit-{{fruit.category }}">{{ fruit }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

{% endblock content %}

While a good and popular convention, there’s nothing that requires anyone to name a base template base.html, nor is there any requirement that if such a template exists, it should be the direct base template at this particular level. Likewise, there’s no requirement that any project templates include a template block named content.

It may fail for people that don’t have a base.html

A more basic template:

<h3>Here is a list of other fruits reported by the app.</h3>

<ul>

{% for fruit in fruit_list %}

<li class="fruit-{{fruit.category }}">{{ fruit }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

Email and Misc Templates#

Email templates are a common feature in apps involving user registration, invitations, and any other kind of outbound notice.

Ensure to keep them in a email/ subfolder

6. Using Static Files#

2 Reasons to include in a standalone app:

- core interface based functionality

- to include static files for the build process - obsolete due to grunt, gulp, webpack and parcek.

- Add a static/ directory within your app directory.

- Add your static files into your new static/ directory.

You must run manage.py collectstatic

Important to include a named subdirectory to prevent name conflicts…eg. static/my_app/css/style.css

For django admin: static/admin/css/myapp.css

If it overrides then use the exact: static/admin/css/login.css

If you use jquery make sure it matches the django version, django admin uses the django.jQuery namespace.

7. Namespacing in your App#

Our entrypoint to namespacing a standalone Django app is the app itself, more specifically, its module name and how it’s named in its AppConfig

Should be descriptive and not overlap with existing namespaces.

When the descriptive name for an app is unavailable or ill-advised because of a conflict, choosing an adapted name with extra context, like stripe_billing, or using a synonym or allusion, works too, like zebra.

Settings#

Remember to namespace specific settings

ORGANIZATIONS_USER_MODEL = AUTH_USER_MODEL

ORGANIZATIONS_USER_LIMIT = 8

ORGANIZATIONS_ADMINS_CAN_INVITE = True

over:

USER_MODEL = AUTH_USER_MODEL

USER_LIMIT = 8

ADMINS_CAN_INVITE = True

Management Commands#

management command names are global

Prefact the command with an identifier or make the command name as descriptive and unique as possible

Template Tags#

- tag library names are global

- individual tags and filters are added into a single namespace

Models and Database Tables#

App models and their respective database table names have default namespaces

Sometimes the database table name should be set correctly:

class LogEntry(models.Model): class Meta: db_table = “activitylogs_logentry

8. Creating a Basic Package#

Turning it into an installable package

If you have a reusable app called blog the parent should look like this:

blog_app

├── blog

├── manage.py

├── runtests.py

├── setup.py

|-- tests

A basic setup.py file#

What is it called, what version is it, where is the code?

from setuptools import setup, find_packages

setup(

name="blog",

version="0.1.0",

author="Ben Lopatin",

author_email="ben@benlopatin.com",

url="http://www.django-standalone-apps.com",

packages=find_packages(exclude=["tests"]),

)

This is enough to build and package it locally.

- Package name: can be omitted but will be called

untitled - Version number critical for bugs and features

- Author name

- author email

- project url: docs, repo

- where the package is found

Setuptools only looks for python files.

To include templates and static files you need to add them to MANIFEST.in

include blog/static/blog/blog.css

recursive-include blog/templates ∗.html

Installing and Using#

You can run python setup.py install which will predictably install a copy of your app into the site-packages directory relevant to your current Python path

Or you can python setup.py develop - this installs a link from site-packages to your project root in the form of a file names blog.egg-info - meaning every change you make is immediately available anywhere you are using the package. Used for exploratory work.